|

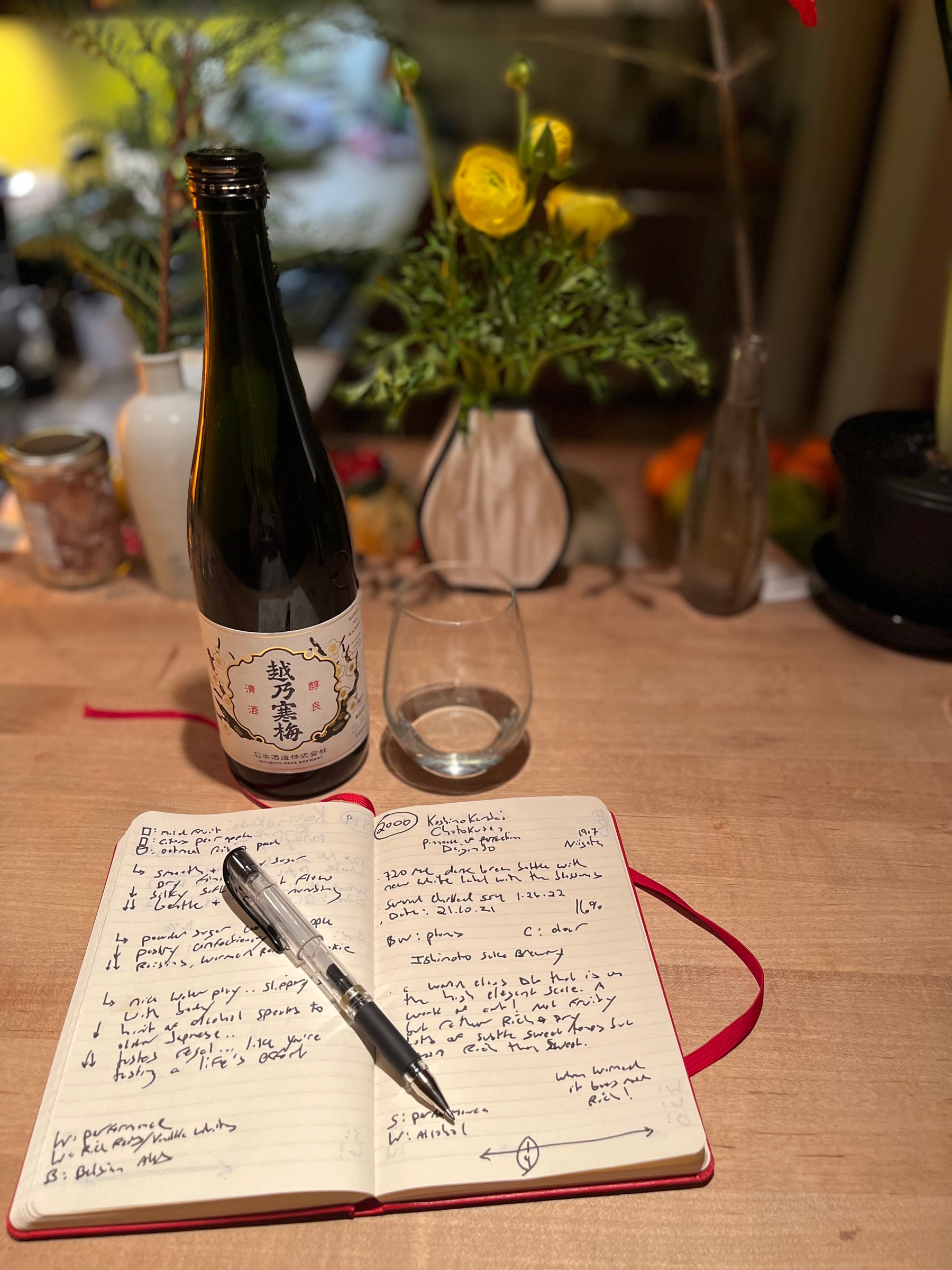

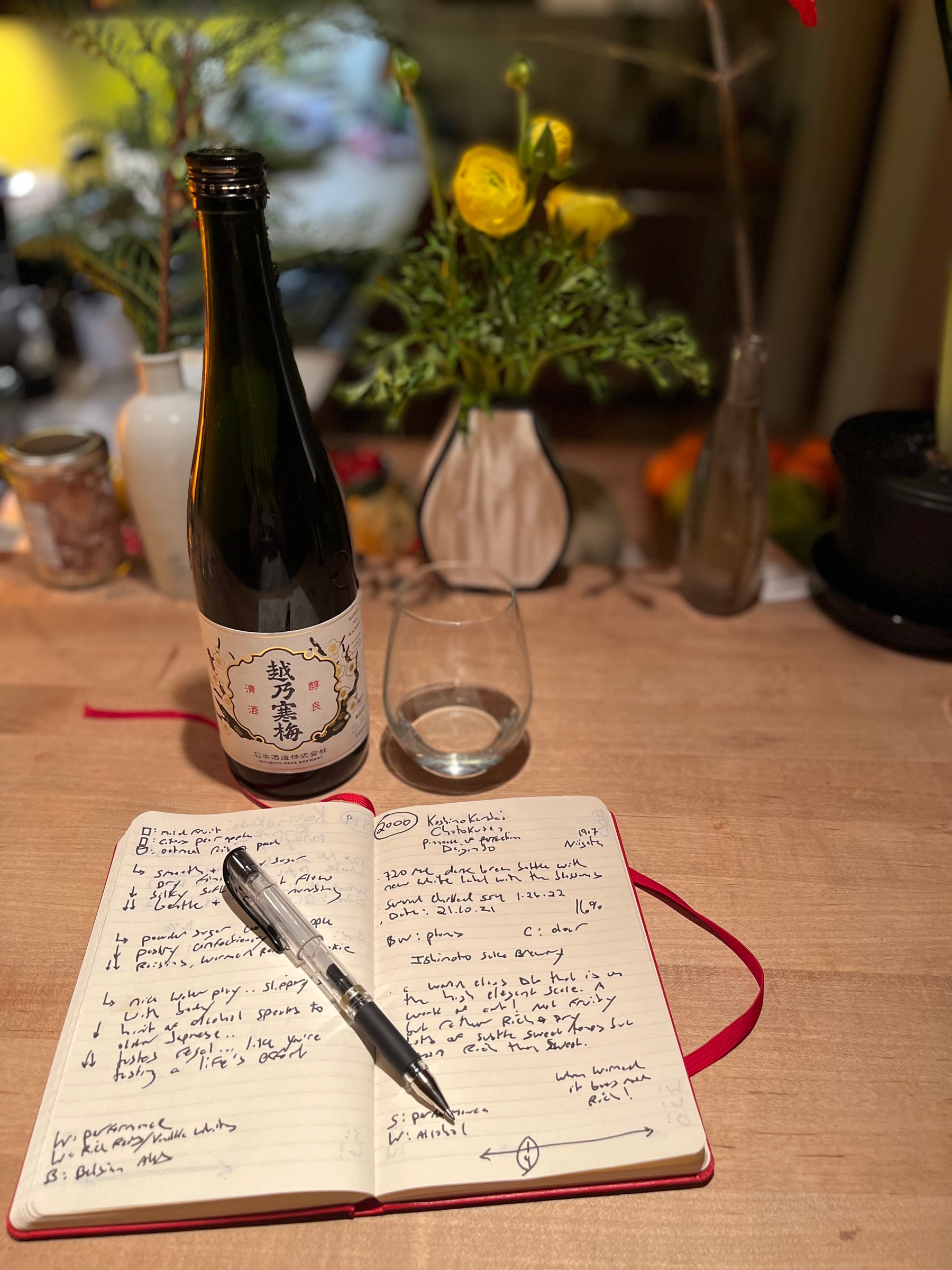

The cool thing is that I didn’t know much about sake, but the brews were my educators, teachers, and sensei. I created my own SMV or Nihonshu-Do system before I even knew what that was and how it was used. I drew a line, a scale if you will, that measured what I felt was the sweetness versus the dryness of each sake. And to be honest I still use my own scale to this day on each and every review knowing full well what the SMV of each sake is that I am reviewing. It’s a grounding mechanism for me, and it does show the sometimes arbitrary use of the Nihonshu-Do that at times doesn’t translate to the actual taste of each brew.

My first entry #1 in book #1 was Kikusui Junmai Ginjo from Niigata prefecture. I started writing the review on the right page, which left the left page blank initially. Later as my reviews enhanced and elongated they carried over to the left page, which is sort of weird. In the first fifty or so reviews I wrote the “Word” that best encapsulated that sake in one descriptive. A sushi chef, Katsu from Sushi on North Beach, sold me a case and said that it was “dry,” but I felt it was fruity and sort of sweet. I gave it a 4 on my sweet and dry scale between 1-10. “Too fruity for a dry Ginjo.” “I say it’s very sweet.” “Better cold than room temp.” And my word was “Citrus.” And I graded it a “B.” What a neophyte!

Tamanohikari, Mu, Tengumai, Maihime, Otokoyama, Kubota, and Suigei were in the first 20 reviews. I gave Kubota Manjyu my first A+, and Urakasumi Zen was my second! The reviews each got a little longer, and my “words” continued to drift in sell mode, and this is even before I thought about opening a sake store. “Smooth as velvet water, no strong flavors, just perfection. This is sake for kings” “This is the Ginjo, and you can really tell the difference from the Daiginjo.” “Dull start with acidic finish, slightly boozy and pretty thick, chewy, syrupy, and a punchy finish.”

|